Privateer and possibly a rum smuggler. Minor hero of the Revolutionary War. Certainly a Freemason, perhaps even a prison warden. That’s our William.

I know I’ve mentioned this guy at family gatherings before, if you’re wondering why he sounds familiar. But let’s be real, I’m not the greatest verbal storyteller on this planet, nor do I have a wonderful memory for dates and places and that sort of thing. So here is William’s story, all written down properly.

Early Life

William Henry Dobbs was born in 1715 or 1716 in New York City, which was of course still part of the British colonies at that point. He was most likely born in his parent’s home near Trinity Church in Manhattan.

His parents were William Dobbs and Catharina Parsell. His father was a shoemaker and a night watchman, as well as a sexton at Trinity Church. He had at least 4 siblings: Adam, Charles, Elizabeth, and Margaret.

First Marriage

William married his first wife, Catharina Van Sise on September 23, 1744 in the New Amsterdam Dutch Reformed Church there in New York City.

They had at least three sons and three daughters together: Anna, Catharina, and Polly, birth dates unknown; Joseph, born circa 1750; William Jr., born sometime between 1750-1755; and Jarvis, born in June of 1755. Sadly, Catharina died soon after the birth of this final child.

Occupation as Mariner

William made his living as a mariner — but it wasn’t always a legitimate sort of business.

In the spring of 1750, he began renting a small wharf lot on Manhattan Island with East River access, fronting Peck Slip in Montgomery Ward. The ward itself no longer exists as such, being now mostly consumed by the South Street Seaport and Two Bridges neighborhoods, but Peck Slip survives as a commercial plaza abutting the Brooklyn Bridge.

Captain William Henry Dobbs was ALLEGEDLY engaged in both licit and unlawful shipping during this time. The Molasses Act of 1733 had made importing sugar, its refined product molasses, and the rum and other spirits derived from it from anywhere other than the British West Indies prohibitively expensive for the Atlantic colonists. Smuggling and bribery were common ways of avoiding the problem; John Hancock himself was one of the most profitable and insolently famous ALLEGED smugglers of the time period.

William was brought up on charges of piracy and smuggling in early of 1756, barely a year after the death of his wife. The typical penalty for a person found guilty of these crimes was death by hanging… but William was instead set to harassing French ships on behalf of the British colonial government. He became an “official” privateer with a British letter of marque. This leniency was most likely due to the ongoing colonial French and Indian War, an extension of the newly-begun Seven Years’ War in Europe.

In June of 1757 William claimed captaincy of the privateer sloop Goldfinch, a 12-gun ship sailed by a crew of 100 men, and he soon sacked his first prize as a licensed privateer. On August 23, 1757, he captured the French brigantine Le Mentor in the Caribbean, just north of the colony of Saint-Domingue on the island of Hispaniola. He also captained the ships Hester and Susanna and Anne during his privateering days.

Second Marriage

As it turned out, 1757 was a significant year for our man. The 41-year-old William Henry Dobbs married the 26-year-old Dorcas Harding at Trinity Church in January of that same year.

Imagine, if you will, being a twenty-something single gal getting a marriage proposal from a dude a decade and a half older than you, with six young children, whose career involves sailing in a real sneaky way around tropical islands and who has just narrowly escaped being hanged for rum-running. Dorcas must have been quite swept off her feet!

Dorcas gave William two more children… albeit after about a decade of marriage, no doubt in part because the man was always away at sea. First came a son, Henry Munro Dobbs, born circa 1766-1767 in New York; he’s the next ancestor on our particular family line. Henry was followed by a daughter, Mary Dobbs, born in August of 1771 — on the island of Curaçao, of all places. It seems that William was eventually persuaded to bring his wife along on his travels to and from the Caribbean.

Occupation as Prison Warden

Interestingly, William probably also served as manager of the New York City Bridewell — a kind of combination jail, debtor’s prison, asylum, and orphanage — from 1767 or 1768 to 1773.

This was not a particularly nice place to be incarcerated. An inquest in May of 1772 into the treatment of a drunkard who had been taken to Bridewell describes a “discipline” that consisted of saltwater for an emetic combined with lamp oil for a laxative, followed by a shot of rum — all of which apparently caused the death the prisoner. Neither William nor the physicians who recommended this treatment were held accountable for this death.

Given that (a) there were a handful of Dobbs uncles and cousins named William scattered around the colony of New York and its waterways, and (b) the Bridewell’s William Dobbs is uniquely identified only as a “mariner”, our William’s claim to the job is merely an educated guess based on his known occupation and his residence in Manhattan just down the street from the prison’s location around that time.

Revolutionary War

When the Revolutionary War started, Captain Dobbs was appointed harbor pilot for the New York Committee of Safety — a kind of off-shoot of the New York Provincial Congress, itself a part of the Continental Congress.

Even though it was one of the original thirteen colonies that collectively declared independence in 1776, New York was actually populated by a significant number of loyalists… particularly New York City, which was occupied by the British military for almost the entirety of the conflict and was therefore a haven for loyalist refugees from rebel-controlled parts of the colonies. Working against the British while living in the midst of them and their supporters was a dangerous proposition.

The Dobbs family’s home on Broadway was destroyed in the Great Fire of New York on September 20, 1776, just days after the British captured the island of Manhattan. Up to a quarter of the city was destroyed by this fire; even the original building of Trinity Church was entirely burned down. Both the loyalists and the rebels accused each other of deliberate arson

William’s work as harbor pilot was based out of Sandy Hook, which is a barrier spit at the main entrance to New York Harbor. Captain Dobbs sent intelligence on the movements of British military ships to and from the city to General George Washington. On one occasion he was dispatched by the mayor of New York City to retrieve his own brother after the British burned the pilot-house on Sandy Hook. He also aided in smuggling gunpowder to rebels remaining in the area and was personally requested as a harbor pilot by General George Washington for a handful of aborted attempts to recapture the city.

I know most folks won’t get all a-flutter over all the dusty old documents that are typical of genealogy research, but this is real fun — Washington’s papers include several letters to and from our William! From these letters we can learn some details about what he was up to during the Revolutionary War… and we can admire his lovely handwriting, too.

Images of the letters are available from Library of Congress. Transcripts are available from Founders Online by the National Archives.

William was nearly captured and was eventually forced to flee with his family north up the Hudson River to a town called Fishkill, where he and his eldest sons continued to assist the Continental Army in the local department of the quartermaster. William was employed for $50 per month as Superintendent of Blacksmiths there, and both he and his sons were tasked with delivery of supplies and correspondence to other rebel camps along the river. By the way, there is now a museum there on the site of the Fishkill Supply Depot.

Death

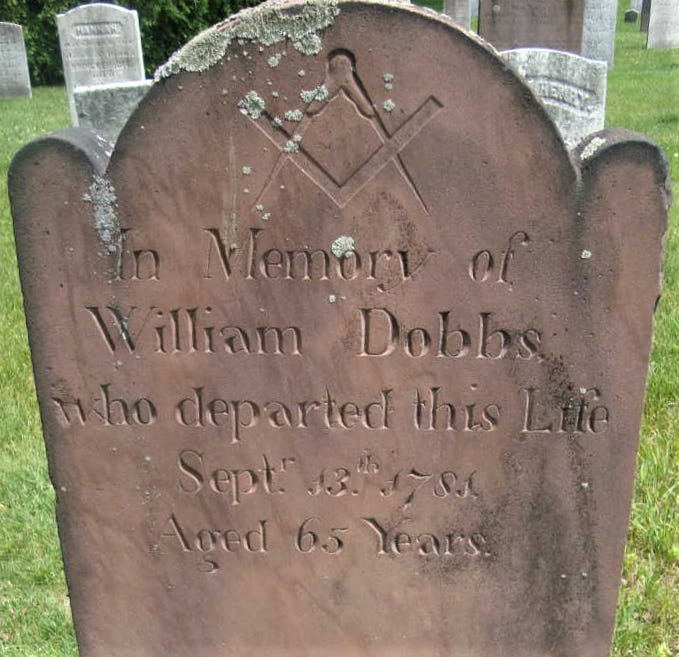

William Henry Dobbs died at age 65 on September 13, 1781 there in upstate New York.

William’s death remains a bit of a mystery. One story provided by a descendent upon her application to the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution posits that he died of a bad case of pneumonia that he contracted while on a secret mission to Rhode Island. One of William’s daughters, Mary “Polly” Dobbs, later testified that she was convinced that Sir Henry Clinton, an officer of the British army, had had Captain Dobbs poisoned to prevent him from helping the rebels any further.

The veracity of these claims and William’s actual cause of death remain uncertain. However, the diaries of George Washington include an entry of July 15, 1781 which records that the British had captured a small ship on the Hudson River and confiscated its cargo that was intended for rebel troops. This ship was captained by William Dobbs of Fishkill — presumably our William. Though Washington does not specify the fate of Dobbs after this misadventure, this does lend some credibility to the cause of his death being caused by one final run-in with the enemy.

William was buried in the cemetery of the Fishkill Reformed Dutch Church. It is from his gravestone that we learn he was a Freemason; it includes a clear carving of the square and compass that identifies members of this group. Since a significant number of the nation’s Founding Fathers were Freemasons — including George Washington and at least a third of the signers of the Declaration of Independence — it should come as no surprise that William Henry Dobbs was one of this brotherhood.

I think William’s life was extremely interesting, and I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about him as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing all this.

And for those readers who manage your own family trees and related documents — a fully cited version (!!!) of this narrative will shortly be added to my files on Ancestry.com and the family’s OneDrive.

Reply to this email or visit tlmk.substack.com to leave a comment if you have any questions or if you have something to say about William!